Martha Henriques

Emmanuel Lafont

Expeditions to the depths of the oceans have revealed strange dark worlds bristling with species new to science – now the race is on to discover them.

If the Earth’s oceans were the size of the island of Manhattan, then oceanographer and deep-sea explorer Edith Widder estimates that we’ve explored the equivalent of perhaps one block – but only at first-floor level.

Oceans make up roughly 99.5% of the planet’s habitats by volume, and within those largely unexplored depths there are thought to be scores of large marine animals unknown to science. When you consider smaller animals too, the number of unknown species rises to the millions.

From 13m-long (43ft) voracious carnivorous squid, to scuttling Yeti crabs huddling near hydrothermal vents, to tusked whales dwelling thousands of feet down to avoid predatory orcas, sizeable marine animals new to science are still being documented every year.

The race to try to find the remaining species is growing urgent. As deep-sea mining threatens to encroach on previously untouched seafloor habitats and climate change warms and acidifies the seas, the ocean’s ecosystems are on the brink of profound change. But with new methods of ocean exploration, we are getting closer than ever to discovering more of the ocean’s giants.

After centuries of ocean exploration, how do we know that we haven’t found all the sizeable ocean animals already?

There are, in fact, several ways that scientists can estimate how many unknown species there are still to be discovered, says Tammy Horton, a taxonomist and ocean biodiversity researcher at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton, UK.

The deep sea is one place where we’re finding lots more new species – Tammy Horton

For instance, imagine taking one small patch of water sitting above the ocean floor a few miles out from the coast, and recording how many new species you find there. Perhaps you see a few crustaceans clinging to a seafloor boulder, several species of fish darting around, and a couple of sediment-feeders embedded in the silty seafloor. Then go back a second time and do it again, making a note of the number of species that you didn’t see there before. Maybe this time a shark swims through your section of water, and you spot one or two other new creatures.

As you go on repeating this process, Horton says, you will tend find fewer and fewer new species. If you plot the number of new species you’ve found on a graph over time (and do “a load of statistical analysis called rarefaction”, Horton adds), you will see a curve that starts out steep as you discover lots of new species, before flattening out towards the horizontal as it reaches what’s called an asymptote – at this point, after many dives to inspect your patch of ocean, you have effectively described everything that lives there.

To get an accurate estimate of how many species there are in the sea, we would need to spend a lot more time there getting samples (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

“If you’re doing that with sharks or with fish, or with mammals, you often get to the asymptote,” says Horton. “They’re bigger, and bigger things get found first. But when you look at sediment samples in the deep sea, or tropical gastropods – little molluscs, tiny things on coral reefs – it never does reach the asymptote. The curve is just going up.”

What that tells us is that there are still countless small sediment-dwellers to discover. But in certain parts of the seas there is a greater chance of finding large animals new to science too.

“There are patterns in species discovery and they are related to size, environment, where we look more often,” says Horton. “The deep sea is one place where we’re finding lots more new species.”

The reason for that is simply that we’ve not spent much time down there. When ambitious expeditions to the deep do happen, they invariably reveal extraordinary unknown worlds.

In Suruga Bay, not far from the Pacific coast of the Japanese island of Honshū, a 1.4m-long (4.6ft) slickhead fish weighing 25kg (55lb) was determined to be a new species in 2021. Most of its closest relatives are nearer 40cm (1.3ft) long, earning this slickhead the name “Yokozuna”, in tribute to the highest rank in sumo wrestling.

This impressive fish was found swimming at depths of around 2,500m (8,250ft), not far from Japan’s largest and most populous island – going out to remoter patches of ocean, still stranger animals may be hiding just out of sight. The problem is, there’s growing evidence that we’ve been seeking them out in the wrong way.

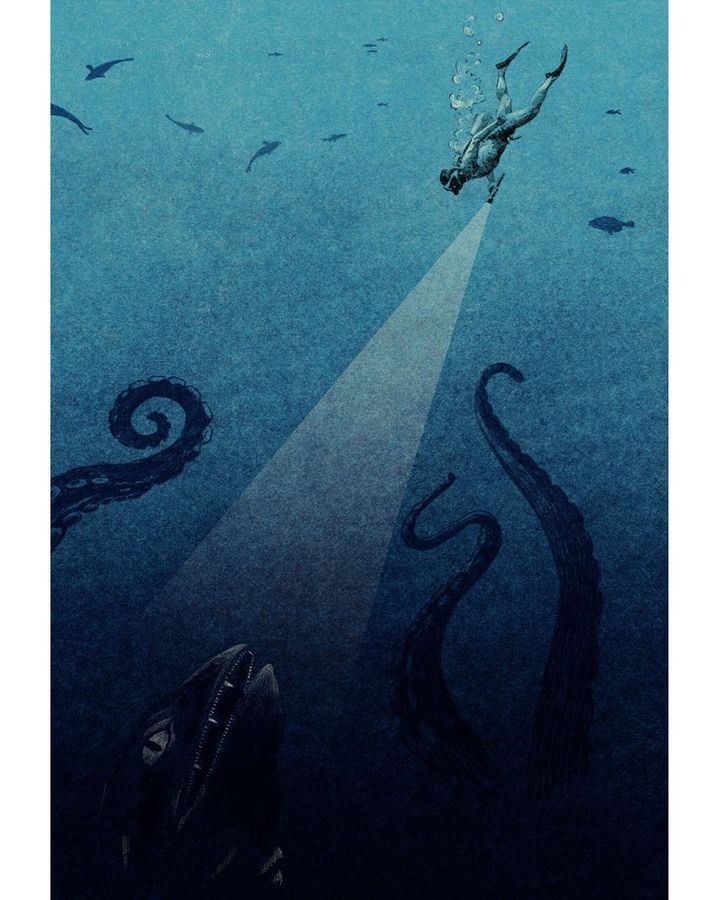

The way we search for the creatures of the deep ocean could be working against us (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

“I make the point all the time that there could be lots of animals in the ocean that we know nothing about because of the way we’ve been exploring,” says Widder. “I spent a lot of my career diving and in submersibles, wondering how many animals there were beyond the range of my lights that could see me, but I couldn’t see them.”

To try to take a look at these elusive creatures, Widder took inspiration from camera traps on land, which use infrared light to take shots of hard-to-track animals such as snow leopards. The infrared cameras don’t disturb the leopards, who can’t see light in that part of the spectrum. But in seawater, infrared light is rapidly absorbed – so Widder had to seek an alternative.

The solution came in the form of a stoplight fish, which has an organ that emits red light under its eye. “So most [deep-sea] animals produce only blue light and see only blue light,” says Widder. “But the stoplight fish is different. It can see and produce blue light, but also red light.”

Curious to find out how the stoplight fish was emitting red light in a world where blue light travelled better in water and was easier to produce, Widder dissected the light organ. She found a filter covering it. “I remember being struck at the time that this filter required a huge amount of energy,” says Widder. “This had to be really important, for some reason.”

Widder took a gamble and decided to have a filter made to imitate that of the stoplight fish. But she wanted not only to test red light in the water, but to see if different patterns of light could attract predators. “I was particularly intrigued by one deep-sea jellyfish, Atolla, which is one of the more spectacular ones. It makes a pinwheel of light. And yet this is a jellyfish that has no eyes, so it’s directed at somebody else. Who, and why?”

With this strange hybrid of the stoplight fish’s filter and the Atolla’s pinwheel of light, Widder deployed her new device. “You can tell what a shoestring operation it was, because you can still see the word ‘Ziploc’ on the electronic jellyfish,” says Widder.

Despite the low budget, it worked. “I put it down right next to a brine pool, which I figured was an oasis that a lot of predators would patrol,” says Widder. The theory was that the Atolla light display acted as a burglar alarm – when the jellyfish was attacked by a predator, it would display its pinwheel lights to try to attract an even bigger predator that would attack its attacker and give the jellyfish a chance to escape.

“For the first four hours, I just had the red light on – I wanted to see how animals responded to it and, for the first time, when the light came on they didn’t swim away,” says Widder. “I was ecstatic – I had my window into the deep sea.”

Four hours later, Widder had programmed the makeshift electronic jellyfish to come on for the first time. “I swear this is true, this never happens in science – but 86 seconds after I turned it on for the first time we recorded a squid over 6ft-long (2m), completely new to science, so new it couldn’t even be placed in any known scientific family.

“You can’t really ask for a better proof of concept than that. That was mind-blowing. People were screaming all over the ship. It was just astonishing.”

The giant squid had been photographed, but it proved extremely hard to film – until oceanographer Edith Wedder devised a new way to seek it out (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

Widder soon set her sights on a much larger squid. “We actually knew that there were millions of giant squid in the ocean because of the number of giant squid beaks found in sperm whale stomachs.” But at the time Widder was doing her experiments, a giant squid had never been caught on film before.

She designed a new version of her electronic “eye in the sea”, which she called the Medusa. Medusa would drift on a 750m-long (2,475ft) line, attached at the surface to a satellite beacon. This way they could leave the eye in the sea for long periods, far from the disturbance of a ship.

Her team threw Medusa out where the giant squid had been sighted before, and where sperm whales were known to feed. As soon as the electronic jellyfish was in the water, it worked. “We got the first video ever recorded of a giant squid in its natural habitat,” says Widder. “And during the course of the expedition, we actually filmed the giant squid five times. And you know this was after how many years of major, major expeditions. They were huge efforts, but we were just doing it wrong.”

The giant squid, Widder notes, is quite a conspicuous animal in the ocean. “They happen to float when they die, because they have ammonia in their tissues,” Widder says. “But what about the stuff that doesn’t float, and that doesn’t end up with beaks in the stomachs of whales? How would we possibly even know it was there?”

All in all, there are thought to be up to two million species living in the oceans, with some estimates putting the figure higher. So far, we know about fewer than 250,000, according to the World Register of Marine Species.

Finding the 1.75 million or so missing species is becoming an increasingly pressing mission – especially in the deepest ocean floors, as the prospect of commercial deep-sea mining becomes imminent.

If we fail to explore remote ocean ecosystems, we may never know the rich biodiversity we risk destroying (Credit: Emmanuel Lafont)

In 2021, the smallest Pacific Island nation of Nauru declared its intention to begin deep-sea mining, triggering a two-year deadline for the International Seabed Authority, the UN body that oversees mining in international waters, to finalise environmental regulations for deep-sea mining.

That deadline of July 2023 is now fast approaching. However, if the ISA’s negotiations are not successful, theoretically deep-sea mining could commence with no environmental regulation this summer. In August 2022, talks ground to a halt after a failure to reach consensus.

A lack of exploration of the seafloor is one reason that there is so much concern about deep-sea mining – we simply don’t know what we’ve got to lose.

Most investigations of life on the seafloor have been fleeting, simply because it is so difficult and expensive to send rovers down to the depths to see what’s there. However, periodic deep-sea investigations have revealed extraordinary ecosystems vastly unlike our own. For instance, deep-sea thermal vents have revealed an immense variety of rare forms of life, such as two-metre-long tube worms, the heaviest in the world, that live on sulphurous bacteria, and long-armed Yeti crabs that cluster near fresh lava flows for warmth.

As deep-sea mining has not yet been commercialised, the kinds of seafloor destruction it would entail are not yet fully known. Some of the most appealing minerals on the seabed are found in the form of polymetallic nodules, known as manganese nodules, which sit on the seafloor surface. These nodules are especially attractive because they contain several valuable metals in a single lump – one nodule might contain considerable quantities of manganese, nickel, copper and cobalt.

One expedition in 2022 went looking for animals on the abyssal seafloor of the central Pacific Ocean. They were looking in an area called the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, which lies between Hawaii and Mexico and stretches to 5,500m (18,150ft) at its deepest. The Clarion-Clipperton Zone has been identified as a potential site for deep-sea mining, as its manganese nodules are found in abundance.

The expedition of the zone’s seafloor life revealed far more than they were expecting. Ovoid creatures with harpoon-like spines and recurved fangs scuttled across the sea floor, while cloud-like tentacled creatures and semi-translucent, eight-fingered polyps clung to rocks or the stalks of glass sponges. Of the 55 species they found, many relatively tiny, they suspected at least 39 were entirely new to science.

Shining light on these diverse ecosystems is especially important given that initial tests have shown they are unlikely to recover easily from mining. One experiment simulating the collection of deep-sea manganese nodules in 1989 showed that the ecosystems that existed between the nodules had still not recovered 26 years later. Suspension-feeders (those that live off food floating in the water) were still significantly reduced in disturbed areas, while deposit-feeders (those that eat food from the sediment), had just about recovered after 26 years. Around the disturbed areas, there was altogether less biodiversity.

If this test was an accurate reflection of mining in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone more broadly, the impacts of mining nodules “may be greater than expected, and could potentially lead to an irreversible loss of some ecosystem functions, especially in directly disturbed areas”, the study authors cautioned.

“Our existence on our planet is dependent on our ability to explore it and understand it, and we haven’t done that,” says Widder. “We are actually destroying the oceans before we know what’s in them. We’ve managed to exploit them, dragging nets and doing deep sea trawling and bottom mining without exploring them. And that’s crazy.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23099575/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_056_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23099556/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_091_Deadly_Bucket_OTHERS_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23099587/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_019_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23101018/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_007_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23101039/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_027_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23101049/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_034_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23101051/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_035_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23103858/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_046_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23101154/FS_laurenowenslambert_deadlybucket_076_Deadly_Bucket_LL_Pick_.jpg)